Tobias Schneebaum, Chronicler and Dining Partner of Cannibals, Dies

Tobias Schneebaum, Chronicler and Dining Partner of Cannibals, Dies

by Margalit Fox (NYT) September 25, 2005

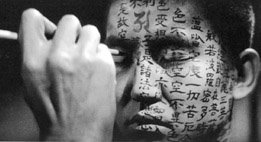

Tobias Schneebaum, a New York writer, artist and explorer who in the 1950's lived among cannibals in the remote Amazon jungle and, by his own account, sampled their traditional cuisine, died on Tuesday in Great Neck, N.Y. He was in his mid-80's and a longtime resident of Greenwich Village.

The cause was complications of Parkinson's disease, his nephew Jeff Schneebaum said. The elder Mr. Schneebaum, who had several nieces and nephews, leaves no immediate survivors.

In 2000, Mr. Schneebaum was the subject of a well-received documentary film, ''Keep the River on Your Right: A Modern Cannibal Tale,'' which follows his return to the Amazon, and to Indonesian New Guinea, where he also lived.

Mr. Schneebaum came to prominence in 1969 with the publication of his memoir, also titled ''Keep the River on Your Right'' (Grove Press). The book, which became a cult classic, described how a mild-mannered gay New York artist wound up living, and ardently loving, for several months among the Arakmbut, an indigenous cannibalistic people in the rainforest of Peru.

Publishers Weekly called the memoir ''authentic, deeply moving, sensuously written and incredibly haunting.'' Other critics dismissed it as romantic, solipsistic and undoubtedly exaggerated.

In either case, Mr. Schneebaum's work raises tantalizing questions about the role of the anthropologist, the responsibilities of the memoirist, and cultural attitudes toward sexuality and taboo. It also offers a look at the persistence of an 18th-century idea -- the Western fantasy of the noble savage -- well into the 20th century.

In 1955, Mr. Schneebaum, then a painter, won a Fulbright fellowship to study art in Peru. There, he vanished into the jungle and was presumed dead. Seven months later, he emerged, naked and covered in body paint. The experience had transformed him, he would later say, but in a way he could scarcely have imagined.

Theodore Schneebaum was born on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, most likely on March 25, 1922 (some sources say 1921), and reared in Brooklyn. Visiting Coney Island as a boy, he was captivated by the Wild Man of Borneo, a sideshow attraction famed for its brute exoticism.

Mr. Schneebaum, who disliked the name Theodore and eventually changed it to Tobias, attended the City College of New York. In 1977, he received a master's in cultural anthropology from Goddard College in Vermont.

As a young man, Mr. Schneebaum was part of New York's flourishing bohemian scene. He studied at the Brooklyn Museum School of Art with the renowned Mexican painter Rufino Tamayo and was gaining recognition for his abstract paintings, shown in New York galleries.

But as a gay man and a Jew in 1950's America, Mr. Schneebaum felt, he often wrote afterward, that there was nowhere he truly belonged. Craving community, he began to travel, and lived for several years in an artists' colony in Mexico.

In 1955, Mr. Schneebaum accepted the fellowship to Peru, hitchhiking there from New York. At a Roman Catholic mission on the edge of the rain forest, he heard about the Arakmbut. (The tribe, whose name is also spelled Harakumbut, was previously known as the Amarakaire. In his memoir, Mr. Schneebaum calls it by a pseudonym, the Akaramas.)

The Arakmbut, whose home was several days' journey into the jungle, hunted with bows, arrows and stone axes. No outsider, it was said, had ever returned from a trip there.

Mr. Schneebaum was not inclined to boldness. In New York, he had once called a neighbor to dispatch a mouse from his apartment. (The neighbor, Norman Mailer, bravely obliged.) But when he heard about the Arakmbut, he set out on foot, alone, without a compass.

''I knew that out there in the forest were other peoples more primitive, other jungles wilder, other worlds that existed that needed my eyes to look at them,'' he wrote in ''Keep the River on Your Right.'' ''My first thought was: I'm going; the second thought: I'll stay there.''

To his relief, the Arakmbut welcomed him congenially. To his delight, homosexuality was not stigmatized there: Arakmbut men routinely had lovers of both sexes. Mr. Schneebaum spent the next several months living with the tribe in a state of unalloyed happiness.

One day, he accompanied a group of Arakmbut men on what he thought was an ordinary hunting trip. The walked until they reached another village. As Mr. Schneebaum watched, his friends massacred all the men there. In the ensuing victory celebration, parts of the victims were roasted and eaten. Offered a bit of flesh, Mr. Schneebaum partook; later that evening, he wrote, he ate part of a heart. It was an experience, he later said, that would haunt him for years. He left the Arakmbut shortly afterward.

''Keep the River on Your Right'' caused a sensation when it was published. Anthropologists were aghast: ethnographers were not supposed to sleep with their subjects, much less eat them. Interviewers were titillated. (''How did it taste?'' a fellow guest asked Mr. Schneebaum on ''The Mike Douglas Show.'' ''A little bit like pork,'' he replied.)

Some critics doubted Mr. Schneebaum's story, though he maintained it till the end of his life. From the documentary film, it is clear that he did live among the Arakmbut. The filmmakers travel with Mr. Schneebaum to Peru and to New Guinea, where he lived for years with the Asmat, a tribe of headhunters and occasional cannibals.

In both places, tribal elders, some of them his former lovers, recognize Mr. Schneebaum and greet him warmly. Neither community is willing to talk about cannibalism. The filmmakers, the brother-and-sister team of David and Laurie Gwen Shapiro, leave the issue deliberately unresolved.

Mr. Schneebaum's other memoirs include ''Wild Man'' (Viking, 1979) and ''Where the Spirits Dwell'' (Grove, 1988). His most recent, ''Secret Places: My Life in New York and New Guinea'' (University of Wisconsin, 2000) moves between the communities he loved: Asmat, now ravaged by globalization, and his friends in Greenwich Village, ravaged by AIDS.

An authority on Asmat art and culture, Mr. Schneebaum was formerly assistant to the curator of the Asmat Museum of Culture and Progress in Agats, Irian Jaya, Indonesia. He was also the author of ''Embodied Spirits: Ritual Carvings of the Asmat.''

I met Tobias Schneebaum when I interviewed him for the Blade when his book Where the Spirit Dwells, about his experiences in Asmat. I'd been very, very influenced by him when I was in college. I read Keep the River on Your Right when I was still anthropology major. I never imagined myself doing field work; I only wished I imagined myself someone who could do that sort of thing. Oddly enough, I think Tobias was the same way until he had experiences that threw him into the arms of head-hunters and cannibals, where, on the whole, he seems to have been comfortable.

Tobias had a very romantic, Whitmanesque vision of gay sex as comradeship that, in practical terms, had much more the feel of a pile of puppies frolicking than of two grooms standing on top of a wedding cake. That vision was around more in the '70s and '80s than recently and Tobias communicated it well because he conveyed it without a lot of complaints about the resistance of Western societies to open eroticism; he made toleration of variation in all kinds of customs seem like obvious common sense. He always said he was terribly uncomfortable about participating in ritual cannibalism but he was very disinclined to characterize that discmfort as grounds for some kind of universal moral code.

When we met we had instant rapport, fed primarily by the exchange of stories on sexual practices around the world--I think I had just finished reviewing a round-up of histories of sex--and I was totally delighted to be tittering in at a cafe table with a guy I thought of as my hero. I wanted him to like me and I was thrilled that he did. Eventually I realized he was one of those people who affected almost everyone the same way; everyone he knew seems to have thought they had a special, intimate bond with him. I only saw him a couple more times in New York. He wrote me once from a cruise ship where he was lecturing on South Pacific flora and fauna. On this voyage, they'd warned him away from lecturing on Fijian sexual practices, which seems a shame, since he knew so many fascinating details about them. I still remember the look on his face as he discussed how Fijian women applied ants to their labia to make them more alluring; it was the look of a grandparent describing something absolutely adorable a grandchild had done.

The week I met Tobias he was on Charlie Rose, who seemed to be trying to get him to express misgivings about sleeping with Asmat men in New Guinea. Tobias' attitude was essentially, for heaven's sake, these people are adults. Uninformed commentators--Melanesian homosexuality is as well-known among anthropologists as ancient Greek homosexuality--focused on the profoundly misguided idea that somehow westerners were introducing western-style decadent practices into the area; but the more insidious idea was that in all encounters between people from industrialized nations and indigenous peoples, the latter are to be regarded as children.

We spent an evening together once at Mary Truitt's; Tobias was a close friend of Mary's mother, Anne Truitt. Mary told me that in her childhood, she was fascinated by the way Tobias would come back from his travels and still seem to carry traces of the wild in his behavior. She hadn't seen him in the years she went from child to adolescent--I think when he was in Borneo--and she said that when he saw her again, he slapped her across the face and said, "You grew up!"

I liked the sound of his voice. I'm glad to have the documentary Keep the River on Your Right because of the footage of him speaking, but I think I'll go back and look at the books now.